Getting plastered

Welcome back! Although we cater for all areas of the museum’s collection here at the Conservation Centre, today I’m going to be talking about dinosaurs again with another update on the Niger Sauropod Project.

Dinosaur bones are often found in a fragile or damaged state, especially in cases like ours, where the bones were discovered weathering out of the rocks in the Sahara. To prevent any further damage, and to ensure they arrived at the museum safely, the field team wrapped them in strips of Hessian soaked in plaster (after first laying on a layer of PVA glue, followed by wet tissue paper, as a barrier between the plaster and the bone). This dried and hardened to form a durable casing that has protected the bones from damage for the last 25 or so years. It’s very similar to how a doctor makes a plaster ‘cast’ to protect a damaged limb.

The 1988 field team transporting the bones safely wrapped in plaster jackets.

Picture courtesy of the NHM Picture Library: http://piclib.nhm.ac.uk/

This method of collecting dinosaur bones is still used today- and hasn’t changed much for more than a hundred years.

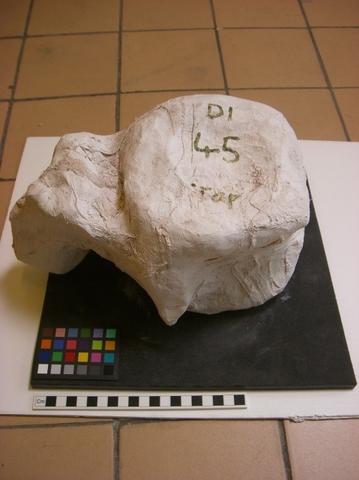

A jacketed-up vertebra just waiting to be freed.

Before we can prepare these bones for research, we have to free them from their jackets. First though, we photograph the specimen, making sure to record the specimen number. Then it’s time to start cutting. We look for a line of weakness where we can start cutting- a variety of tools can be used for this, but we’ve found scalpels and Stanley knives most effective.

Cutting off the field jackets can produce a lot of plaster dust, so sometimes using a face mask is a good idea. If it looks like the bone underneath is fragmentary or has major breakages, then half of the jacket can be left on for now to provide support while we work on stabilising the specimen.

Erica carefully cutting away the plaster jacket. Note the mini vacuum

cleaner to remove plaster dust

Once the bone is freed from its jacket then preparation can commence.... but I’ll leave that for a future update.

Kieran Miles is a science educator with a background in palaeobiology. He has been with the Conservation Centre for nearly two years and hasn’t broken anything important (yet).